Clinical Update - Secondary Prevention of ARF Fact Checked

The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease (3rd edition) contains clinical information based on national and international best practice. The information is supported by a cultural framework to highlight the importance of how care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD) can be both clinically sound, and culturally safe.

There are several opportunities for intervention - prevention along the ARF-RHD disease pathway; including primordial prevention of group A streptococcal (Strep A) infections, primary prevention of ARF, secondary prevention of ARF, and tertiary prevention of complications associated with RHD. In this article, we take a closer look at secondary prevention, and specifically secondary prophylaxis for ARF, with a focus on delivery of benzathine benzylpenicillin G injections.

ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS FOR ARF

Secondary prophylaxis for acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is the consistent and regular administration of antibiotics to prevent group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus (Strep A) infections and recurrent ARF.

|

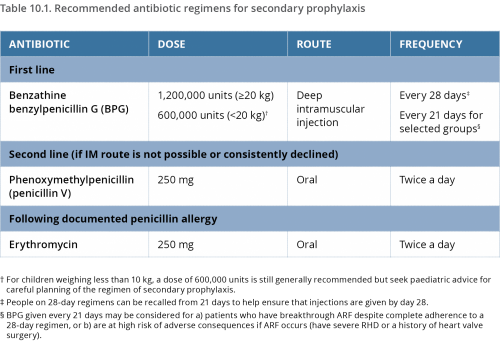

Recommended regimen

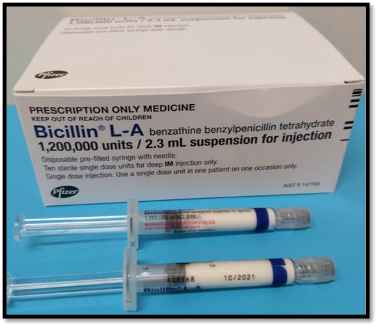

Regular antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for people who are highly suspected or confirmed to have ARF, and for people who have RHD.1,2 The most effective method is deep intramuscular, long-acting benzathine benzylpenicillin (BPG) injections every 21 to 28 days.3

In Australia, BPG is available in a pre-filled syringe which needs to be refrigerated.

Each injection needs to be given no later than day 28 after the last injection, because without the ongoing protection of the penicillin, there is a high risk of another Strep A infection and recurrent ARF. BPG injections are safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and should continue if indicated.4 BPG should also continue after heart valve surgery.

Oral penicillin is not as effective as BPG5,6,7 because oral administration achieves less predictable serum penicillin concentrations.8 Twice-daily tablets, every day, are also more difficult for many people to adhere to over many years.9

Erythromycin tablets are available for people who have a confirmed penicillin allergy. (True penicillin allergy is rare, so suspected allergy needs to be carefully investigated)

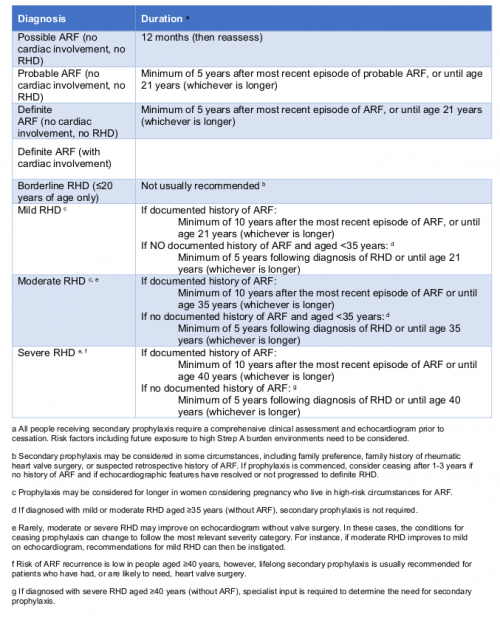

Duration of secondary prophylaxis

Recommendations for duration of secondary prophylaxis are made by balancing the risk of ARF recurrence and its consequences, against the difficulties associated with delivering and receiving regular injections.

For most people, injections continue into early adulthood. Duration at an individual level depends on several factors including age, diagnosis (of ARF or RHD) and severity of RHD if it is present, ongoing level of risk of recurrent ARF, and potential harm to the heart from a future ARF illness. It must first be confirmed that there is no ongoing symptomatic deterioration, and that existing RHD is stable. Therefore, careful review by a specialist and echocardiographic assessment are required before stopping secondary prophylaxis.10

| Ultimately, ceasing secondary prophylaxis is a decision between an individual and their medical specialist based on a detailed medical assessment and the expected risk of ARF recurrence. |

Recommendations for duration of secondary prophylaxis based on diagnosis classification. (Information derived from the 2020 Guideline Table 10.2)

The recommended duration of secondary prophylaxis has changed from 10 years11 to five years for people with highly suspected and confirmed ARF, if there is no cardiac involvement or established RHD. The implication of this change is that people aged less than 16 years at the time of their ARF diagnosis, who did not have cardiac involvement and have normal follow-up echocardiography, can cease treatment earlier. This is based on the likelihood of an older person developing RHD, when their last ARF episode was five or more years ago and did not affect the heart, is very low. (The recommendation to continue to age 21, if that is longer, still applies)

| If a person is aged over 35 years at the time of RHD diagnosis and there is no documented history of ARF, then secondary prophylaxis is not recommended. |

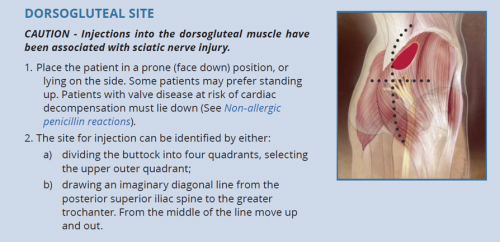

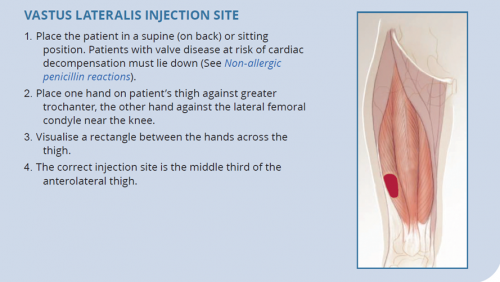

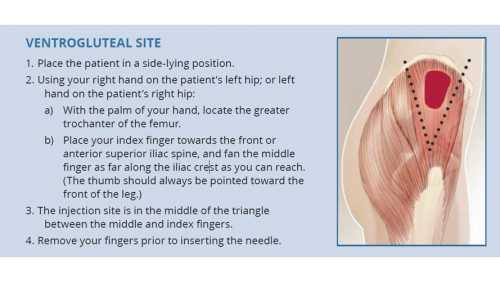

Sites of injection

Ideally, health staff should be competent to administer injections into all recommended sites so that people receiving injections have options, based on their individual circumstances.

- The dorsogluteal (buttock) and vastus lateralis (thigh) muscles are traditional sites for deep intramuscular injection.12 However, care should be taken with the dorsogluteal site given its proximity to the sciatic nerve.

- The ventrogluteal (hip) muscle is emerging as a preferred site among some health workers and their patients.13,14

| The deltoid (upper arm) is not recommended for BPG administration. |

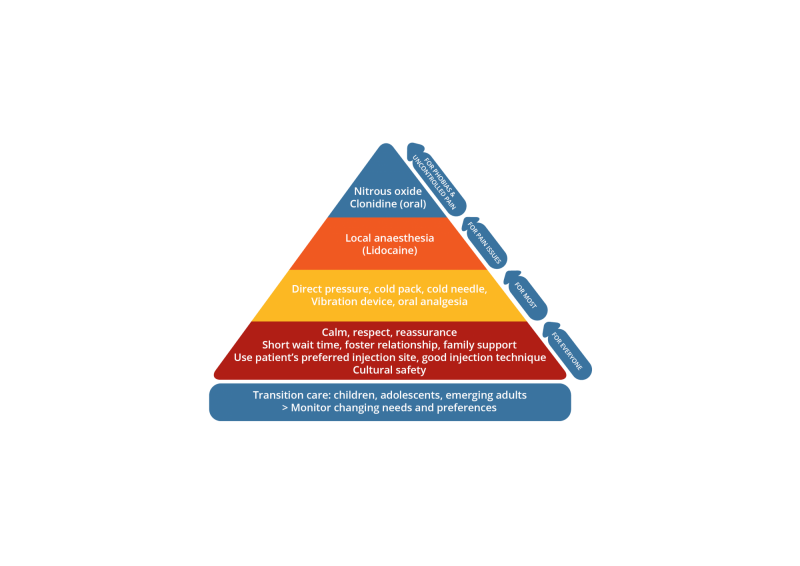

Managing pain and distress

Intramuscular BPG injections can be painful, and the pain, fear and distress associated with the first injection can affect a person’s expectations of future injections. Most people who experience pain do not get used to them without some intervention.15,16

Injection pain management is presented as a hierarchy of strategies based on level of intervention required. There are non-pharmacological strategies for everyone,17 distraction techniques and analgesia if pain is an issue, and protocols for procedural sedation for people with uncontrolled pain or needle phobias.18

| Underpinning the management of pain and distress should be an environment based on privacy, respect, cultural safety, and prompt, skilled service. |

Lidocaine

Lidocaine-Claris (lignocaine) is a sodium-channel-blocking drug. It is quick-acting and lasts 60 to 90 minutes. When used with BPG injections, it is reported to reduce pain during injection and in the first 24 hours after injection.19,20

In line with local policy, lidocaine can be offered as part of a multifaceted approach to managing injection pain. However, it should only be used following discussion between the individual and their doctor, with input from family and relevant health staff.

| Lidocaine can also be administered as a spray or cream to anaesthetise the skin, but this is not effective in anaesthetising lower dermal or fat layers. |

Consider:

- the impact of introducing lidocaine for someone who does not normally have it - the additional volume of the lidocaine may itself cause pain.

- the impact of not providing lidocaine for someone who usually has it could result in an uncomfortable injection, and influence that person’s attitude to future injections.

- the patient’s preferred site of injection and method of pain relief (if required) may change over time.

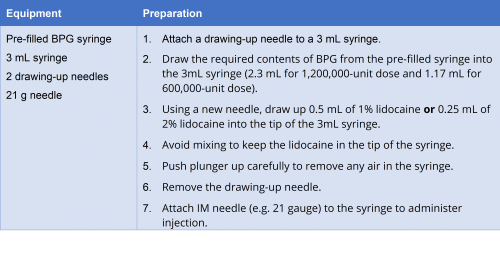

Administering BPG with lidocaine†

(Adapted from Heart Foundation New Zealand, 2014)21

† Check local policies: recommendations for the use of lidocaine with BPG vary across Australia.

Sedation

Two options have been presented in the 2020 guideline; pre-mix nitrous oxide (Entonox) and oral clonidine

- Pre-mixed nitrous oxide is an S4 (restricted) medicine. It is a gas mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen which is delivered through a mask. It must be used on prescription only and with sound knowledge of potential adverse effects.22 Nitrous oxide should not be used in children aged less than 4 years, or in older children who are unable to self-administer. Nitrous oxide may not be available in rural and remote settings.

- Oral clonidine is an alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist with broad cardiovascular and central nervous system effects including analgesia and sedation. Clonidine produces ‘a calm patient who can be easily aroused to full consciousness’.23 Immediate-release clonidine reaches a peak concentration within 60-90 minutes. However, drug effects also include dry mouth, bradycardia and hypotension. People with RHD may not tolerate hypotension or bradycardia; so discussion with the medical specialist, baseline observations and close post-procedural monitoring is required in all instances.

- 1. Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland K, Weber M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2005; 5(11): 685-694. View Source

- 2. Steer A, Carapetis JR. Prevention and treatment of rheumatic heart disease in the developing world. Nature Review Cardiology, 2009. 6; 689-698. View Source

- 3. Manyemba J, Mayosi BM. Penicillin for secondary prevention of rheumatic fever (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002 3: CD002227. View Source

- 4. Department of Health Therapeutic Goods Administration. Medicines and TGA classifications. 2019. View Source

- 5. Feinstein A, Wood HF, Epstein JA, et al. A controlled study of three methods of prophylaxis against streptococcal infection in a population of rheumatic children. II. Results of the first three years of the study, including methods for evaluating the maintenance of oral prophylaxis. New England Journal of Medicine, 1959. 260(14): 697-702. View Source

- 6. World Health Organization. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: report of a WHO expert consultation, Geneva, 29 October–1 November 2001. WHO Technical Report Series 923, 2004. View Source

- 7. Kassem A, et al. Guidelines for management of children with rheumatic fever (RF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD) in Egypt, The Egyptian Society of Cardiology and the Egyptian Society of Pediatric Cardiologists: Alexandria.

- 8. Wood H, Feinstein AR, Taranta A, et al. Rheumatic fever in children and adolescents. A long term epidemiological study of subsequent prophylaxis, streptococcal infections and clinical sequelae. III. Comparative effectiveness of three prophylaxis regimes in preventing streptococcal infections and rheumatic recurrences. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1964. 60(S5): 31-46. View Source

- 9. Dajani A. Adherence to physicians’ instructions as a factor in managing streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatrics, 1996. 97(6): 976-80.

- 10. RHDAustralia (ARF/RHD writing group). The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease (3rd edition); 2020. View Source

- 11. RHDAustralia (ARF/RHD writing group). The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease (3rd edition); 2020.

- 12. Ogston-Tuck S. Intramuscular injection technique: an evidence-based approach. Nursing Standard 2014; 29(4): 52-59. View Source

- 13. Brown J, Gillespie M, Chard S. The dorso-ventro debate: in search of empirical evidence. British Journal of Nursing 2015; 24(22): 1136-1139. View Source

- 14. Stephenson M. Evidence Summary. Intramuscular Injection: Site Selection. The Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database, JBI@Ovid. 2019; JBI20991.

- 15. Mitchell AG, Belton S, Johnston V, et al. Aboriginal children and penicillin injections for rheumatic fever: how much of a problem is injection pain? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 2018; 42: 46-5. View Source

- 16. Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Management of Procedure-related Pain in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2006. 42: S1-S2. View Source

- 17. Leroy P, Costa L, Emmanouil D, van Beukering A, Franck L S. Beyond the drugs: nonpharmacologic strategies to optimize procedural care in children. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 2016; 29(1): S1-S13. View Source

- 18. Hartling L, Milne A, Foisy M, et al. What Works and What’s Safe in Pediatric Emergency Procedural Sedation: An Overview of Reviews. Academic Emergency Medicine 2016; 23: 519-530. View Source

- 19. Russell K, Nicholson R, Naidu R. Reducing the pain of intramuscular benzathine penicillin injections in the rheumatic fever population of Counties Manukau District Health Board. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 2014; 50: 112-117. View Source

- 20. Amir J, Ginat S, Choen YH, et al. Lidocaine as a diluent for administration of benzathine penicillin G. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 1998; 17(10): 890-893. View Source

- 21. Dajani A. Adherence to physicians’ instructions as a factor in managing streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatrics, 1996. 97(6): 976-80.

- 22. Short duration Entonox® for administration of Benzathine Penicillin (Bicillin). Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service, Queensland Government, Australia. 2017.

- 23. Basker S, Singh G, Jacob R. Clonidine in paediatrics - a review. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia 2009; 53(3): 270-280.