Clinical update - tertiary prevention of RHD complications

TERTIARY PREVENTION OF RHD COMPLICATIONS

The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease (3rd edition) contains clinical information based on national and international best practice. The information is supported by a cultural framework to highlight the importance of how care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD) can be both clinically sound, and culturally safe.

In this article, we hightlight some key elements of tertiary prevention; management of RHD.

Principles of RHD management

The aim of RHD management is to prevent (at least delay) complications, disability, and the need for heart valve surgery and premature death. People living with RHD require regular and timely follow-up to monitor for recurrence of ARF, to manage cardiac symptoms and conduct interventions, and for the administration of secondary prophylaxis.

Recommendations for the type and frequency of care are provided in the 2020 guideline. While these recommendations help to guide best practice, patient management should always be interpreted through a clinical decision lens following medical assessment. Individualised care plans should be based on the needs of the individual in terms of the specific valve lesion/s and severity of symptoms, as well as the individual’s capacity for self-management and treatment preferences.

Access to care

Having RHD is usually a life-long experience, and everyone living with RHD need access to experienced health practitioners and trusted and skilled others who can support them. Multidisciplinary teams should include the person with RHD and members of their family, together with nurses, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health staff for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander patients, and experienced health practitioners who have training or expertise with RHD management. These specialist health practitioners include physicians, paediatricians and general practitioners. People with severe RHD, particularly where there are complex health issues, should also have direct involvement with a cardiologist. An obstetrician and midwife must also be part of the team for pregnant women with RHD.

Echocardiography and dental services are critical elements of RHD management, however, providing timely services to people living in rural and report areas of Australia can be difficult. While there has been expansion of outreach services over recent years, access to specialist services is still inadequate in some areas.1 Some promising work has been done globally towards upskilling local non-experts to perform abbreviated echocardiograms, 2,3 and while this model is gaining traction for community screening purposes, it does not currently contribute broadly to routine follow up echocardiograms for people with established disease.

Some of the highest rates of RHD are in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people aged between 10 and 25 years. For many in this age group, privacy and discretion are critical elements in their decision to seek health care, and they will forgo healthcare around sensitive issues if they are not assured of confidentiality. 4 Transition from child to adult health services requires careful planning and involvement from the whole team, through a culturally-safe and trust-building process, to prevent interruptions to care and loss to follow up.

The World Health Organisation has developed helpful guidelines to support transition of care for adolescents5 (Table 11.4) which have been adapted for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Secondary prophylaxis

Antibiotic prophylaxis underpins management of RHD by preventing recurrences of ARF. The 2020 guideline edition includes changes to the duration of secondary prophylaxis for some groups who do not have a documented history of ARF (Table 10.2):

- Mild RHD - if no documented history of ARF and aged less than 35 years, prophylaxis is required for a minimum of 5 years following diagnosis of RHD or until age 21 years (whichever is longer)

- Moderate RHD - if no documented history of ARF and aged less than 35 years, prophylaxis is required for a minimum of 5 years following diagnosis of RHD or until age 35 years (whichever is longer)

- Severe RHD – if no documented history of ARF, prophylaxis is required for a minimum of 5 years following diagnosis of RHD or until age 40 years (whichever is longer)

It is important to note that a decision to cease secondary prophylaxis under these circumstances should be considered very carefully after a comprehensive assessment of the person and their future risk of developing ARF. A plan for ensuring timely echocardiography monitoring after cessation needs to be built in to the decision (Table 10.2).

Other considerations:

|

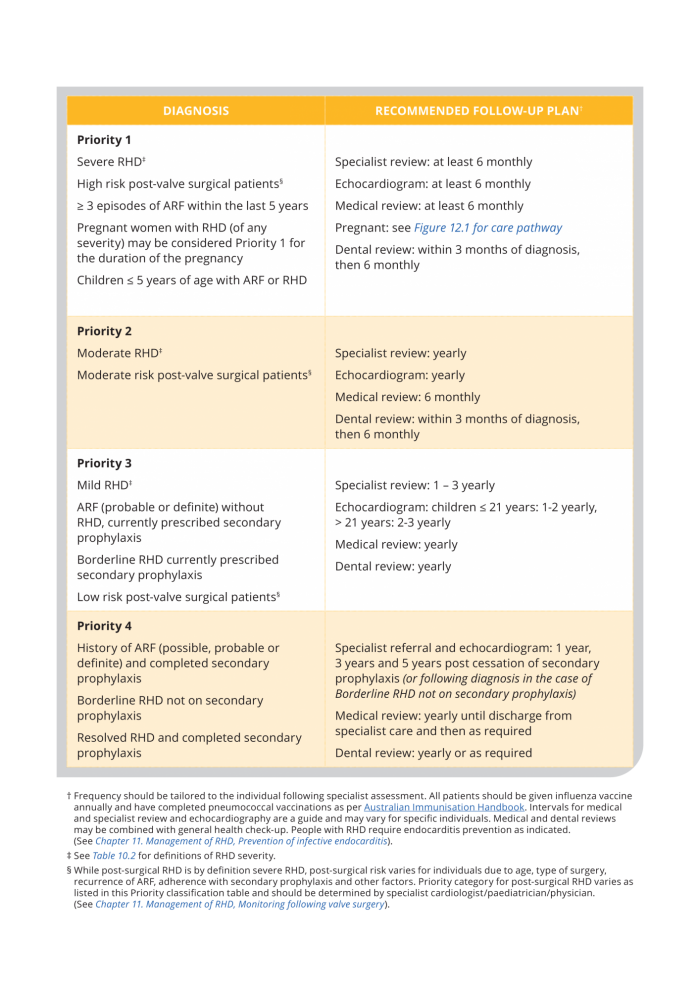

Priority classification and recommended follow-up

Recommended follow-up plans for RHD have been developed for Australia’s high-risk population based on disease severity - Priority classification (Table 11.2, and below). Frequency of each element of care needs to be tailored to the needs of the individual, which may change over time. Where necessary services are not reliable, these recommendations should be used to advocate for equitable access on behalf of those needing care.

Table 11.2. Priority classification and recommended follow-up

“There’s a need to make more informative resources for RHD clients. I felt there was a lack of information for young women in regard to pregnancy and having RHD. Young women and girls want answers to questions like, ‘am I putting myself at risk if I want to have a baby?’” - Champion, RHDAustralia Champions4Change program, 2019.

Many women with RHD can safely conceive and have children, and to do this safely, women and girls with RHD need a lot of support. For women who do want to have children there needs to be a focus around timing of pregnancy, which may need to be coordinated with timing of surgery, and planning needs to start when they are young. The information in Table 12.1 on pages 241 – 243 of the 2020 guideline includes a detailed pathway of care, including transition of girls with RHD to adult health services, preconception planning, attention during pregnancy, labour and birth, and management of pregnant women who have received mechanical valves (replacement) and require anticoagulation.

The ability to give birth on traditional lands holds cultural importance for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Unfortunately, for many women with RHD, this ability to ‘birth on country’ is complicated by the need for high level medical care during and after delivery, so is often not considered safe. The modified World Health Organization classification of maternal cardiovascular risk (mWHO)6 is a useful tool to assess the level of specialist care management required during pregnancy, and has been successfully applied in low-resource settings. Again, forward planning and careful management is required for successful birthing on country.

Timing of surgery

Surgical intervention for damaged heart valves is available to everyone in Australia, and repeat surgeries are not uncommon. As with all aspects of RHD management, factors to consider with surgery are very much based on the needs and capacity of the individual, including

- Age at first operation and continued growth in children (if applicable).

- For women – the desire for future pregnancy and the associated risks.

- The person’s preference and their physical obligations after surgery (e.g. they may work in physically demanding environments).

- Adherence to care including medical appointments, regular secondary prophylaxis and other medications and interventions.

- Access to health services – including specialist services - in the post-operative period for anticoagulation monitoring, and medication management.

- Presence and severity of mixed and multi-valve disease.

- Contraindications to anticoagulation (e.g. prior significant bleeding complications or bleeding conditions) which may complicate surgery and post-operative management.

Infective endocarditis prevention

Infective endocarditis is infection of the endocardial aspect of the heart. Endocarditis results in high morbidity and mortality.7,8 Symptoms include fever, rigors, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, myalgias, arthralgias, night sweats and abdominal pain. Endocarditis commonly affects damaged or prosthetic valves, which is why RHD poses such a significant risk.

Prophylaxis for endocarditis is now recommended for all people with RHD rather than being restricted to only high-risk populations with RHD. Table 11.5 on page 223 of the 2020 guideline includes a list of the high-risk procedures requiring endocarditis prophylaxis.

Antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent infective endocarditis following dental procedures now favours amoxicillin instead of clindamycin. This includes people receiving regular penicillin-based prophylaxis (benzathine benzylpenicillin G). Additional amoxicillin given at the time of the procedure provides the required drug level to prevent bacteraemia from mouth organisms. However, for people who are currently or have recently taken a course of other beta-lactam therapy at treatment dose (not benzathine benzylpenicillin at the prophylactic dose), commensal organisms may have developed resistance, so a non–beta-lactam antibiotic, such as clindamycin, is recommended for endocarditis prophylaxis. Antibiotics are usually given within 60 minutes of a high-risk procedure (see Table 11.6).

Oral health management

Poor oral health, particularly the presence of dental caries, increases the risk of infective endocarditis. Regular oral health review and support is therefore an important part of standard RHD management. Patients should also receive age- and culturally appropriate education to maintain oral health in the longer term.

|

Everyone living with RHD needs regular dental review to reduce the risk of infective endocarditis. Preparation for heart valve surgery must include comprehensive dental consultation and management of dental caries, gum disease and oral health generally.9 |

Historically, people arriving at hospital for heart valve surgery have been sent home without surgery, because dental preparation has not been satisfactory. Dental review and management preceding cardiac surgery therefore requires detailed planning and coordination, particularly for people living in rural and remote areas who may have limited access to dental services. Multiple appointments may be needed if multiple extractions and fillings are required. If oral health has not been maintained as part of routine RHD management, it should be addressed as soon as possible after the decision to proceed with surgery.

Summary

Management of RHD requires consideration of the person; their circumstances, the ongoing risk of ARF, previous and future potential for disease complications, cultural needs, and their capacity to access care. RHD management should be reviewed regularly to ensure that it is still relevant to the individual’s changing needs.

- 1. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing (2008). Report on the Audit of Health Workforce in Rural and Regional Australia, April 2008. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

- 2. Francis JR, Fairhurst H, Whalley G, et al The RECARDINA Study protocol: diagnostic utility of ultra-abbreviated echocardiographic protocol for handheld machines used by non-experts to detect rheumatic heart disease BMJ Open 2020;10: e037609.

- 3. Ploutz M, Lu JC, Scheel J, et al. Handheld echocardiographic screening for rheumatic heart disease by non-experts. Heart. 2016 Jan;102(1):35-39.

- 4. Ford C, English A, Sigman G. Confidential Health Care for Adolescents: position paper for the society for adolescent medicine. The Journal of Adolescent Health 2004; 35(2): 160-167.

- 5. World Health Organization & Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global standards for quality health-care services for adolescents: a guide to implement a standards-driven approach to improve the quality of health care services for adolescents. Volume 2: Implementation guide. Geneva, 2015

- 6. Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. European Heart Journal 2018; 39(34): 3165-3241.

- 7. Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD. Infective endocarditis. The Lancet 2016; 387(10021): 882-893.

- 8. Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 132(15): 1435-86.

- 9. Silvestre FJ, Gil-Raga I, Martinez-Herrera M, et al. Prior oral conditions in patients undergoing heart valve sur Prior oral conditions in patients undergoing heart valve surgery. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry. 2017;9(11): e1287-1291.